Triplet Loss

One way to learn the parameters of the neural network so that it gives you a good encoding for your pictures of faces is to define an applied gradient descent on the triplet loss function.

Let's see what that means.

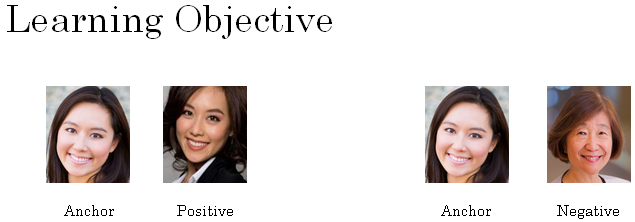

To apply the triplet loss, you need to compare pairs of images.

For example, given one pair of images, you want their encodings to be similar because these are the same person. Whereas, given another pair of images, you want their encodings to be quite different because these are different persons.

In the terminology of the triplet loss, what you're going do is always look at one anchor image and then you want to distance between the anchor and the positive image - meaning as the same person to be similar.

Whereas, you want the anchor when pairs are compared to the negative example for their distances to be much further apart.

So, this is what gives rise to the term triplet loss, which is that you'll always be looking at three images at a time. You'll be looking at an anchor image, a positive image, as well as a negative image. And I'm going to abbreviate anchor positive and negative as A, P, and N.

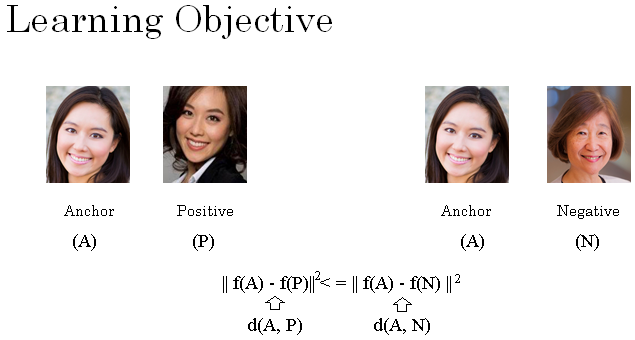

So to formalize this, what you want is for the parameters of your neural network of your encodings to have the following property, which is that you want the encoding between the anchor minus the encoding of the positive example, you want this to be small and in particular, you want it to be less than or equal to the distance of the squared norm between the encoding of the anchor and the encoding of the negative

And you can think of d as a distance function, which is why we named it with the alphabet d.

Now, if we move to term from the right side of this equation to the left side, what you end up with is \( ||f(A) - f(P)||^2 - ||f(A) - f(N)||^2 \leq 0 \), you want this to be less than or equal to zero.

But now, we're going to make a slight change to this expression, which is one trivial way to make sure this is satisfied, is to just learn everything equals zero.

If f always equals zero, then this is zero minus zero, which is zero. And so, well, by saying f of any image equals a vector of all zeroes, you can almost trivially satisfy this equation.

So, to make sure that the neural network doesn't just output zero for all the encoding, so to make sure that it doesn't set all the encodings equal to each other.

Another way for the neural network to give a trivial output is if the encoding for every image was identical to the encoding to every other image, in which case, you again get zero minus zero. So to prevent a neural network from doing that, what we're going to do is modify this objective to say that, this doesn't need to be just less than or equal to zero, it needs to be quite a bit smaller than zero.

So, in particular, if we say this needs to be less than negative alpha, where alpha is another hyperparameter, then this prevents a neural network from outputting the trivial solutions.

And by convention, usually, we write plus alpha instead of negative alpha there. And this is also called, a margin, which is terminology that you'd be familiar with if you've also seen the literature on support vector machines, but don't worry about it if you haven't.

And we can also modify this equation on top by adding this margin parameter \( ||f(A) - f(P)||^2 - ||f(A) - f(N)||^2 + \alpha \leq 0 \).

So to give an example, let's say the margin is set to 0.2. If in this example, d of the anchor and the positive is equal to 0.5, then you won't be satisfied if d between the anchor and the negative was just a little bit bigger, say 0.51.

Even though 0.51 is bigger than 0.5, you're saying, that's not good enough, we want a d(f(A, N)) to be much bigger than d(f(A, P)) and in particular, you want this to be at least 0.7 or higher.

Alternatively, to achieve this margin or this gap of at least 0.2, you could either push this up or push this down so that there is at least this gap of this alpha, hyperparameter alpha 0.2 between the distance between the anchor and the positive versus the anchor and the negative.

So that's what having a margin parameter here does, which is it pushes the anchor positive pair and the anchor negative pair further away from each other.

So, let's take this equation we have here at the bottom, and formalize it, and define the triplet loss function.

So, the triplet loss function is defined on triples of images. So, given three images, A, P, and N, the anchor positive and negative examples. The positive examples is of the same person as the anchor, but the negative is of a different person than the anchor.

We're going to define the loss as follows. The loss on this example, which is really defined on a triplet of images is, let me first copy over what we had previously.

So, that was \( ||f(A) - f(P)||^2 - ||f(A) - f(N)||^2 + \alpha \). And what you want is for this to be less than or equal to zero. So, to define the loss function, let's take the max between this and zero. \( \text{Loss} = max(||f(A) - f(P)||^2 - ||f(A) - f(N)||^2 + \alpha , 0) \)

So, the effect of taking the max here is that, so long as this is less than zero, then the loss is zero, because the max is something less than equal to zero, when zero is going to be zero.

So as you've achieved the objective of making term \( ||f(A) - f(P)||^2 - ||f(A) - f(N)||^2 + \alpha \) less than or equal to zero, then the loss on this example is equals to zero.

But if on the other hand, if the term \( ||f(A) - f(P)||^2 - ||f(A) - f(N)||^2 + \alpha \) is greater than zero, then if you take the max you would have a positive loss.

So by trying to minimize this, this has the effect of trying to send the thing \( ||f(A) - f(P)||^2 - ||f(A) - f(N)||^2 + \alpha \) to be less than or equal to zero.

And then, so long as there's zero or less than or equal to zero, the neural network doesn't care how much further negative it is.

So, this is how you define the loss on a single triplet and the overall cost function for your neural network can be sum over a training set of these individual losses on different triplets. \( J = \sum_{i = 1}^{m} L(A^{(i)}, P^{(i)}, N^{(i)}) \)

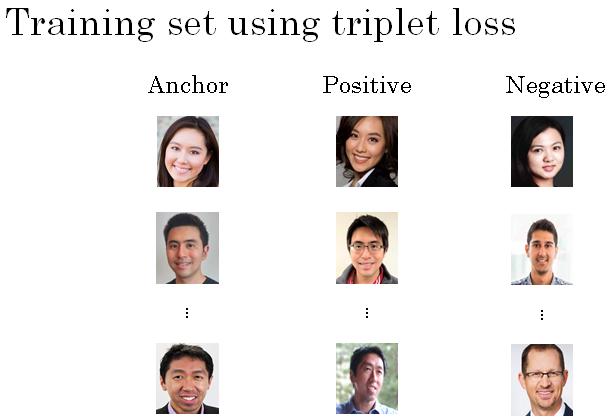

So, if you have a training set of say 10,000 pictures with 1,000 different persons, what you'd have to do is take your 10,000 pictures and use it to generate, to select triplets like this and then train your learning algorithm using gradient descent on this type of cost function, which is really defined on triplets of images drawn from your training set.

Notice that in order to define this dataset of triplets, you do need some pairs of A and P - Pairs of pictures of the same person.

So the purpose of training your system, you do need a dataset where you have multiple pictures of the same person. That's why in this example, I said if you have 10,000 pictures of 1,000 different person, so maybe have 10 pictures on average of each of your 1,000 persons to make up your entire dataset.

If you had just one picture of each person, then you can't actually train this system.

But of course after having trained the system, you can then apply it to your one shot learning problem where for your face recognition system, maybe you have only a single picture of someone you might be trying to recognize.

But for your training set, you do need to make sure you have multiple images of the same person at least for some people in your training set so that you can have pairs of anchor and positive images.

Now, how do you actually choose these triplets to form your training set? One of the problems if you choose A, P, and N randomly from your training set subject to A and P being from the same person, and A and N being different persons, one of the problems is that if you choose them so that they're at random, then this constraint is very easy to satisfy.

Because given two randomly chosen pictures of people, chances are A and N are much different than A and P.

But if A and N are two randomly chosen different persons, then there is a very high chance that d(A, N) will be much bigger than the d(A, P).

And so, the neural network won't learn much from it. So to construct a training set, what you want to do is to choose triplets A, P, and N that are hard to train on.

So in particular, what you want is for all triplets that this constraint be satisfied. So, a triplet that is hard will be if you choose values for A, P, and N so that maybe d(A, P) is actually quite close to d(A,N).

So in that case, the learning algorithm has to try extra hard to take \( ||f(A) - f(P)||^2 \) and try to push it up or take this thing on the left \( ||f(A) - f(N)||^2 \) and try to push it down so that there is at least a margin of alpha between the left side and the right side.

And the effect of choosing these triplets is that it increases the computational efficiency of your learning algorithm.

If you choose your triplets randomly, then too many triplets would be really easy, and so, gradient descent won't do anything because your neural network will just get them right, pretty much all the time.

And it's only by using hard triplets that the gradient descent procedure has to do some work to try to push these quantities further away from those quantities.

And if you're interested, the details are presented in this paper by Florian Schroff, Dmitry Kalinichenko, and James Philbin, where they have a system called FaceNet, which is where a lot of the ideas I'm presenting in this video come from.

By the way, this is also a fun fact about how algorithms are often named in the deep learning world, which is if you work in a certain domain, then we call that blank. You often have a system called blank net or deep blank. So, we've been talking about face recognition. So this paper is called FaceNet, and in the last section, you just saw Deepface.

But this idea of a blank net or deep blank is a very popular way of naming algorithms in the deep learning world. And you should feel free to take a look at that paper if you want to learn some of these other details for speeding up your algorithm by choosing the most useful triplets to train on, it is a nice paper.

So, just to wrap up, to train on triplet loss, you need to take your training set and map it to a lot of triples.

So, below is our triple with an anchor and a positive, both for the same person and the negative of a different person. Here's another one where the anchor and positive are of the same person but the anchor and negative are of different persons and so on.

And what you do having defined this training sets of anchor positive and negative triples is use gradient descent to try to minimize the cost function J we defined on an earlier section, and that will have the effect of that propagating to all of the parameters of the neural network in order to learn an encoding so that d of two images will be small when these two images are of the same person, and they'll be large when these are two images of different persons.

So, that's it for the triplet loss and how you can train a neural network for learning and an encoding for face recognition.

Now, it turns out that today's face recognition systems especially the commercial face recognition systems are trained on very large datasets.

Datasets north of a million images is not uncommon, some companies are using north of 10 million images and some companies have north of 100 million images with which to try to train these systems. So these are very large datasets even by modern standards, these dataset assets are not easy to acquire. Fortunately, some of these companies have trained these large networks and posted parameters online.

So, rather than trying to train one of these networks from scratch, this is one domain where because of the share data volume sizes, this is one domain where often it might be useful for you to download someone else's pre-train model, rather than do everything from scratch yourself.

But even if you do download someone else's pre-train model, I think it's still useful to know how these algorithms were trained or in case you need to apply these ideas from scratch yourself for some application. So that's it for the triplet loss.

In the next section, I want to show you also some other variations on siamese networks and how to train these systems. Let's go onto the next section.